All Memory is Prelude: Part II

II. The Road from Charleston to Charlottesville, Essays from ‘Monuments’ Project

(Researched and written 2016-2019)

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Calhoun Street/Mother Emanuel Way, Charleston, South Carolina 2018

June 17, 2015, our nation was in anguish after nine African American members of a bible study were murdered in a mass shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.[1]

The State Senator and senior pastor of the church, Rev. Clementa Pinckney was among those whose lives were lost that day; as was Tywanza Sanders, the youngest victim at 26 years old.[2] They were killed by a young white man, who the congregants welcomed in to join their bible study, before he opened fire.

The assailant held white supremacist beliefs that, in the judicial proceedings that followed the killings, were proven to be overtly motivated by racial hatred.[3]

The tragic event was a painful jolt to the nation, but unfortunately not at all inconsistent with American history. As one of the oldest independent black congregations in the South, the Emanuel AME congregation in Charleston had endured violent attacks from its beginnings. In the 1820's, dozens of parishioners were executed and the church was burned down by a white mob after members were accused of participating in the Denmark Vesey's legendary conspiracy to organize an insurrection of enslaved peoples in the city, forcing the congregation to meet in secret until after the Civil War. [4] [5]

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Calhoun Street/Mother Emanuel Way, Charleston, South Carolina 2018

Following the vicious killings in that summer of 2015, photographs became publicized of the murderer posing with the Confederate flag, a symbol not uncommonly displayed in our nation, particularly in the South.[6] The geography of the mass shooting site was also historically tied to this Confederate symbol. Not only was South Carolina the first state to declare secession from the Union, but only miles from the Emanuel AME church are the waters where the first shots of the Civil War were ordered by Confederate General G.T. Beauregard, 154 years earlier.[7]

The Confederate flag's symbolic connection to the slaying and the murderer's far-right beliefs was a sobering reminder of the sinister, violent and repressive history of the flag. Yet, as a society, most have come to accept the presentation of Confederate symbols. Some ignore, feel bewildered by or bitterly resent the modern displaying of these extraordinarily loaded symbols of racial oppression. Many feel indifferent, while some others revere them. These symbols simultaneously represent a source of historic pride for some and a source of historic pain for others.

It is a profound divide of American historical remembrance. But in the midst of a resurgence of white supremacist domestic terrorism, the extreme consequences of this divide were again proving to be fatal.

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Calhoun Street/Mother Emanuel Way, Charleston, South Carolina 2018

Though Charleston is historically regarded for its significance as the site of the first battle of the Civil War and as a Confederate secessionist stronghold, its history as a site of liberation and memorializing of the "martyrs" who fought for freedom is unsurprisingly less intertwined in the beautiful city's historic allure.

In March of 1865, the enslaved people of Charleston were liberated by the Union Army's Twenty-first U.S. Colored regiment. Soon after their arrival, these black soldiers would proudly march in a parade organized by the city’s recently emancipated residents to honor the war heroes, as large crowds cheered and sang along its procession. Weeks later, a celebration took place on Fort Sumter; four years to the day after it was captured by Confederate troops, three thousand liberated African Americans would honor the Union victory. The following year, our nation's first ever Memorial Day was organized and observed by the black residents of Charleston. Ministers from all the black churches of the city dedicated the ceremony and a procession of thousands of "black schoolchildren (newly enrolled in freedmen's schools) marched…each with an armload of roses and singing ‘John Brown's Body.’”[8]

The legacy of the Confederacy and, with it, the legacy of white supremacy, has historically never been without active resistance or a fight to reclaim public memory, nor would it in the present.

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in

Calhoun Street/Mother Emanuel Way, Charleston, South Carolina 2018

Ten days after the shooting in Charleston, activist Brittany Newsome scaled the flag pole on a Confederate monument outside the South Carolina statehouse and removed the Confederate flag that had been flown on the grounds for over half a century.[9] The flag had been reinstated at the South Carolina capitol during the Civil War centennial as a response to the Civil Rights movement, with the intention of being a symbolic rebuke to progressive state lawmaker's efforts toward racial equality.[10] [11]

Newsome was arrested following her protest, but her act of civil disobedience would help begin a reckoning on public tribute to the Confederate flag and the cult of the “lost cause.”[12] The act emphasized a long standing question: how is it that these Confederate symbols which stood for preserving the institution of slavery, white supremacy and the violent repression of African Americans are displayed in honor in contemporary America's public spaces?

On July 10th, 2015, in light of the slaying and the grassroots-led, rekindled reexamination of commonplace confederate symbols, Governor Nikki Haley ordered the removal of the Confederate flag from the South Carolina state capitol grounds. She stated that the "area [..] belongs to everyone…No one should drive by the statehouse and feel pain, no one should ever drive by the statehouse and feel like they don’t belong.”[13]

This public reexamination of Confederate symbols became a national debate following these events. People and politicians across the country called for the removal of honorary tributes to the Confederacy. The public protest, lengthy legal proceedings and eventual removal of four monuments in New Orleans (the subject of the ‘Monuments’ photo essay) drew national attention. In other parts of the country, protesters tore down Confederate symbols in grassroots acts of civil disobedience.[14] It seemed to be a true cultural and historical pivot from the past.

The movement was immediately met with backlash.

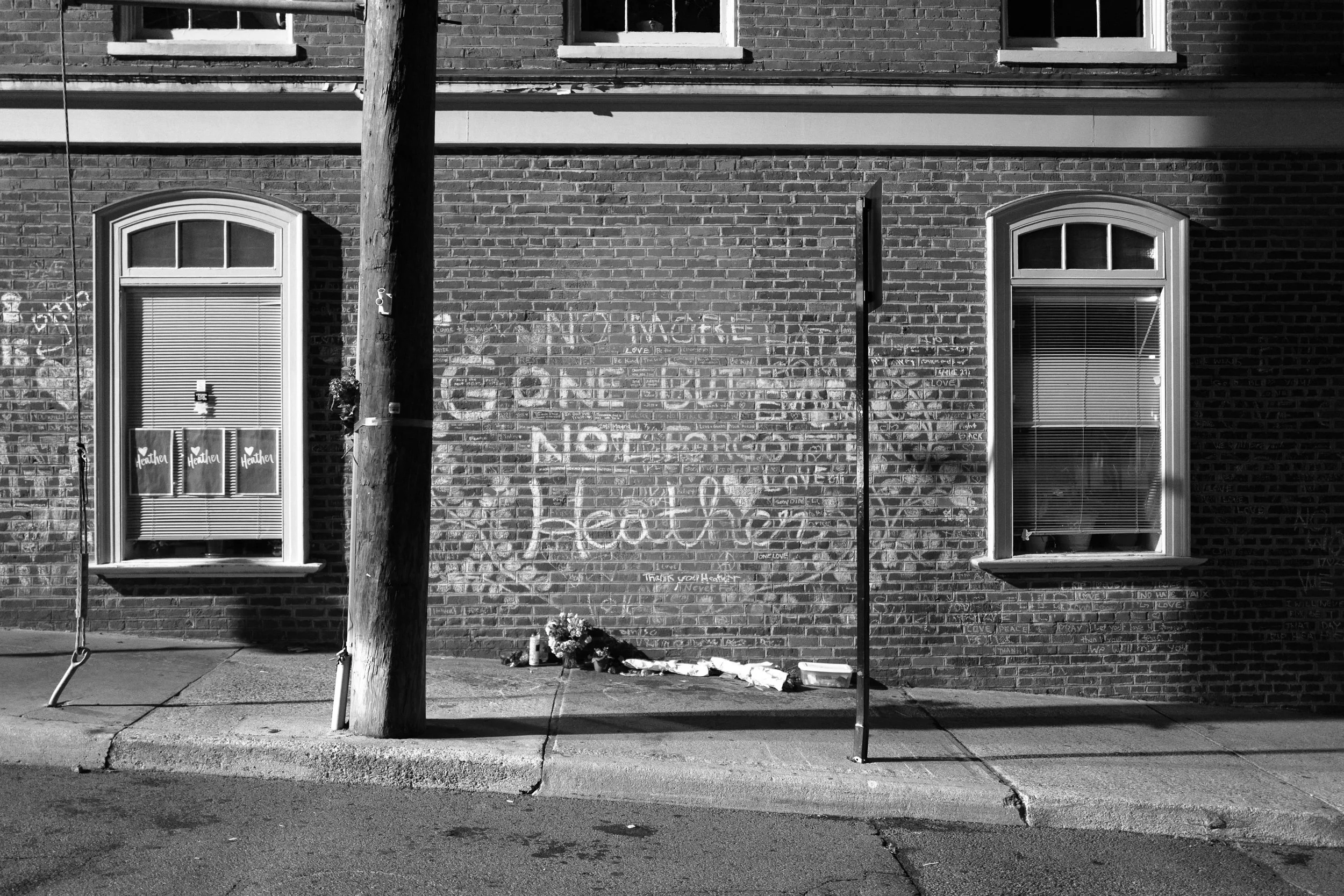

4th Street/Heather Heyer Way, Charlottesville, VA 2018

Outraged counter-protesters across the country began to fight to preserve these symbols of the Confederacy. Many aligned state legislatures reacted by attempting to pass laws outlawing the removal of these symbols. They also pushed strict penalties for protesters who vandalized or attempted to remove these symbols through acts of civil disobedience.[15]

These politicians and counter-protesters claimed that removal of these displays would be "erasing history" and Southern heritage. They argued that their removal would be disrespecting the soldiers who honorably died fighting— many of these same monument defenders were descendents of such soldiers. They felt the Confederate leaders honored in these statues were being wrongfully judged by modern standards. They also sternly argued that these symbols did not honor the cause of slavery or white supremacy, but the “lost cause” of state's rights.

These are much of the same justifications that have been made in defending the "rebel" flag and confederate monuments in America's post Civil Rights era. But the stated motivations for honoring Confederate symbols have changed quite a bit since they began to flourish in the repressive "Redemption" or Jim Crow era. The most obvious discrepancy from those eras to modern rhetoric: nearly any racial component whatsoever. Despite this racist oratory being edited out of modern defenses to honor the Confederacy, its essence was still very much present.

Although the fervent public defense of Confederate symbols was largely spearheaded by zealots, these are historical beliefs that are not solely held by extremists.

Much of the rhetoric surrounding the “lost cause” are beliefs held by average, well intentioned folk across our country, who largely condemn racial bigotry. Yet, despite what others would see as overwhelming contrary evidence to their beliefs, their common understanding of the Confederacy is one of gallantry.

The call to defend Confederate symbols was not vigorously heeded by this general populous who may have empathized with their preservation. But the battle cry was enthusiastically heard by white supremacists and far right militants of all stripes. In many ways, the cause would reinvigorate and galvanize organizations of racial hatred and even bring some into mainstream relevance.

In these years, white supremacist groups faced off with protesters during events calling for the removal of Confederate symbols across the nation, as did anti-racist protesters at events held to defend Confederate monuments by white supremacists. Violent confrontation was practically inevitable.

4th Street/Heather Heyer Way, Charlottesville, VA 2018

August 12, 2017, in the midst of a tense battle over the planned removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, VA, a Neo-Nazi rammed his car into a group of anti-hate protesters, injuring 19 people and killing 32 year old Heather Heyer.[16] Two Virginia state troopers were also killed in a helicopter crash that was deployed in the midst of the state of emergency.[17] The emergency declaration by the Governor had been prompted by large scale violent confrontations between protesters, many of whom were brandishing firearms in the open carry state. There were also several reports of attacks and violent intimidation toward citizens of Charlottesville by white supremacist groups who had migrated to the city for the "Unite the Right" rally.[18]

The events in Charlottesville had already made their way into the national news before the detestable murder of Heyer took place. The night prior, disturbing video was reported of swarms of white supremacists wielding torches while marching through the University of Virginia campus, chanting lines such as "Jews will not replace us," "white lives matter" and the Nazi mantra "blood and soil."[19] The tragic events were followed by two days of silence on the matter by President Trump before he condemned any of the white supremacist violence. But he would soon qualify the condemnation in his now infamous line that there were "very fine people, on both sides."[20]

Many of these white supremacist groups were already enthusiastic supporters of the president and incorporated his "Make America Great Again" regalia into their attire. The president had more than flirted with white nationalist rhetoric and included “Alt-Right” strategists in his inner circle, earning him the support of many far-right organizations.[21] The president's statement, in context of the interview where he supported the preservation of Confederate monuments, was interpreted as a winking endorsement of these extremists' cause and behavior and worked to further garner their loyalty.

4th Street/Heather Heyer Way, Charlottesville, VA 2018

Nikki Haley, the Republican governor who helped to begin the institutional removal of Confederate symbols, had early on disavowed candidate Trump for not condemning his received support by the Ku Klux Klan and their former leader David Duke. Still, after his win, she would accept a role in Trump's presidential cabinet.[22]

The mentioned Neo-Nazi, David Duke, who was a high profile attendee of the same "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, invoked Trump's slogan in a message to the white supremacists present: “We are determined to take our country back. We are going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump. That’s what we believed in, that’s why we voted for Donald Trump."[23] Duke would run in the Republican primaries for Senator of Louisiana in 2016 on the coattails of Trump's popularity and the strife surrounding the Confederate monuments in New Orleans. Duke already had a long record of violent incidents around Confederate monuments in New Orleans, having been arrested for inciting a riot at Lee Circle as far back as 1972.[24] While the likes of Duke and alt-right groups were growing more emboldened, the incendiary rhetoric of the 45th president would also help to accelerate grassroots anti-racist organizations and institutional efforts to remove these Confederate symbols across the nation.

Divisions of historical remembrance and contemporary political calculation continued to be intrinsically intertwined.

4th Street/Heather Heyer Way, Charlottesville, VA 2018

Notes

[1] "Charleston Church shooting." History. 6/8/20. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/charleston-ame-church-shooting

[2]Kreutz, Liz, et al. "Charleston Shooting Leaves 9 Dead at AME Church, Gunman in Custody." ABC News. 6/18/15. https://abcnews.go.com/US/charleston-shooting-leaves-dead-ame-church-gunman-remains/story?id=31845305

[3] "Charleston Church shooting." History. 6/8/20. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/charleston-ame-church-shooting

[4] "Our Story: Brief History of Emanuel-Official." Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. https://motheremanuel.com/our-story

[5] Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, (Bold Type Books: New York, 2016) 149-150

[6]"What we know about the shooting at a Charleston Church that left nice dead." The Washington Post. 6/18/15.https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/national/charleston-church-shooting/

[7]Dupuy, Ernest R. and Trevor N. Dupoy, The Compact History of the Civil War, (New York: Hawthorn Books Inc, 1960) p. 23

[8] David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001) p.66, 67,69

[9] Davis, Linsey. "Woman Who Removed Confederate Flag at SC Statehouse: 'Enough is Enough'." ABC News. 7/2/15.https://abcnews.go.com/US/woman-removed-confederate-flag-sc-statehouse/story?id=32176372

[10]"History of the Confederate battle flag in South Carolina." Dayton Daily News. 7/10/15.https://www.daytondailynews.com/news/local-govt--politics/history-the-confederate-battle-flag-south-carolina/2bsBKR3jpoSAep0whDM8BK/

[11] "Confederate Flag Removed From South Carolina Capitol Grounds." Huffpost/Reuters. 7/10/15. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/confederate-flag-removal_n_7769300

[12] Davis, Linsey. "Woman Who Removed Confederate Flag at SC Statehouse: 'Enough is Enough'." ABC News. 7/2/15.https://abcnews.go.com/US/woman-removed-confederate-flag-sc-statehouse/story?id=32176372

[13] "Confederate Flag Removed From South Carolina Capitol Grounds." Huffpost/Reuters. 7/10/15. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/confederate-flag-removal_n_7769300

[14]Graham, David A. "Durham's Confederate Statue Comes Down." The Atlantic. 8/15/17. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/08/durhams-civil-war-monument-and-the-backlash-to-the-backlash/536889/

[15]Park, Madison. "Removal of Confederate monuments stirs backlash in statehouses." CNN. 5/12/17.https://www.cnn.com/2017/05/12/us/confederate-monument-state-bills/index.html

[16] Almasy, Steve and Chandrika Narayan. "Heather Heyer died 'fighting for what she believed in'." CNN. 12/16/17 https://www.cnn.com/2017/08/13/us/charlottesville-heather-heyer-profile/index.html

[17]"Unite the Right Rally Charlottesville Timeline." Facing History and Ourselves. 12/1/18. https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/Unite_the_Right_Rally_in_Charlottesville_Timeline.pdf

[18] Aster, Hannah. "The Charlottesville "Unite the Right" Rally." Shortform. 7/19/21. https://www.shortform.com/blog/charlottesville-unite-the-right-rally/

[20] Holan, Angie Drobnic. "In Context: Donald Trump's 'very fine people on both sides' remarks (transcript)." POLITIFACT. 4/26/19. https://www.politifact.com/article/2019/apr/26/context-trumps-very-fine-people-both-sides-remarks/.

[21]Chait, Jonathan. "Donald Trump Building Team of Racists." New York. 11/18/16. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2016/11/donald-trump-building-team-of-racists.html

[22] "Trump Picks Nikki Haley For UN Ambassador." Huffpost/Reuters. 11/23/16. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-picks-nikki-haley-for-un-ambassador_n_5835975ee4b000af95ed5188

[23] Hanson, Hillary. "Ex-KKK Leader David Duke Says White Supremacists Will 'Fulfill' Trump's Promises." Huffpost. 8/12/17. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/david-duke-charlottesville-rally-trump_n_598f3ca8e4b0909642974a10

[24] Shen, Aviva. "The history behind New Orleans' long fight to remove its Confederate monuments." Think Progress. 3/13/18. https://archive.thinkprogress.org/new-orleans-fight-confederate-monuments-1596a7d2618d/)