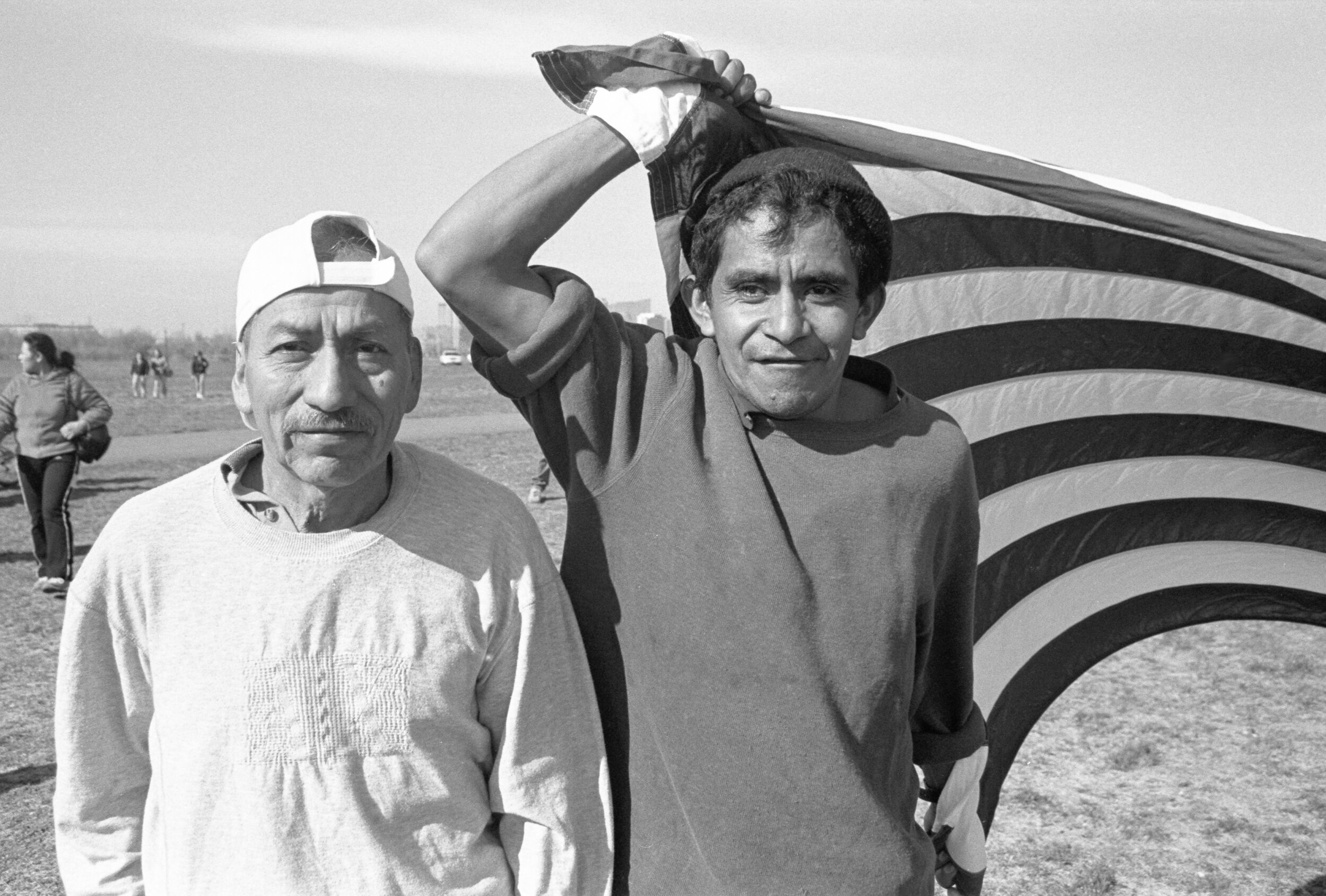

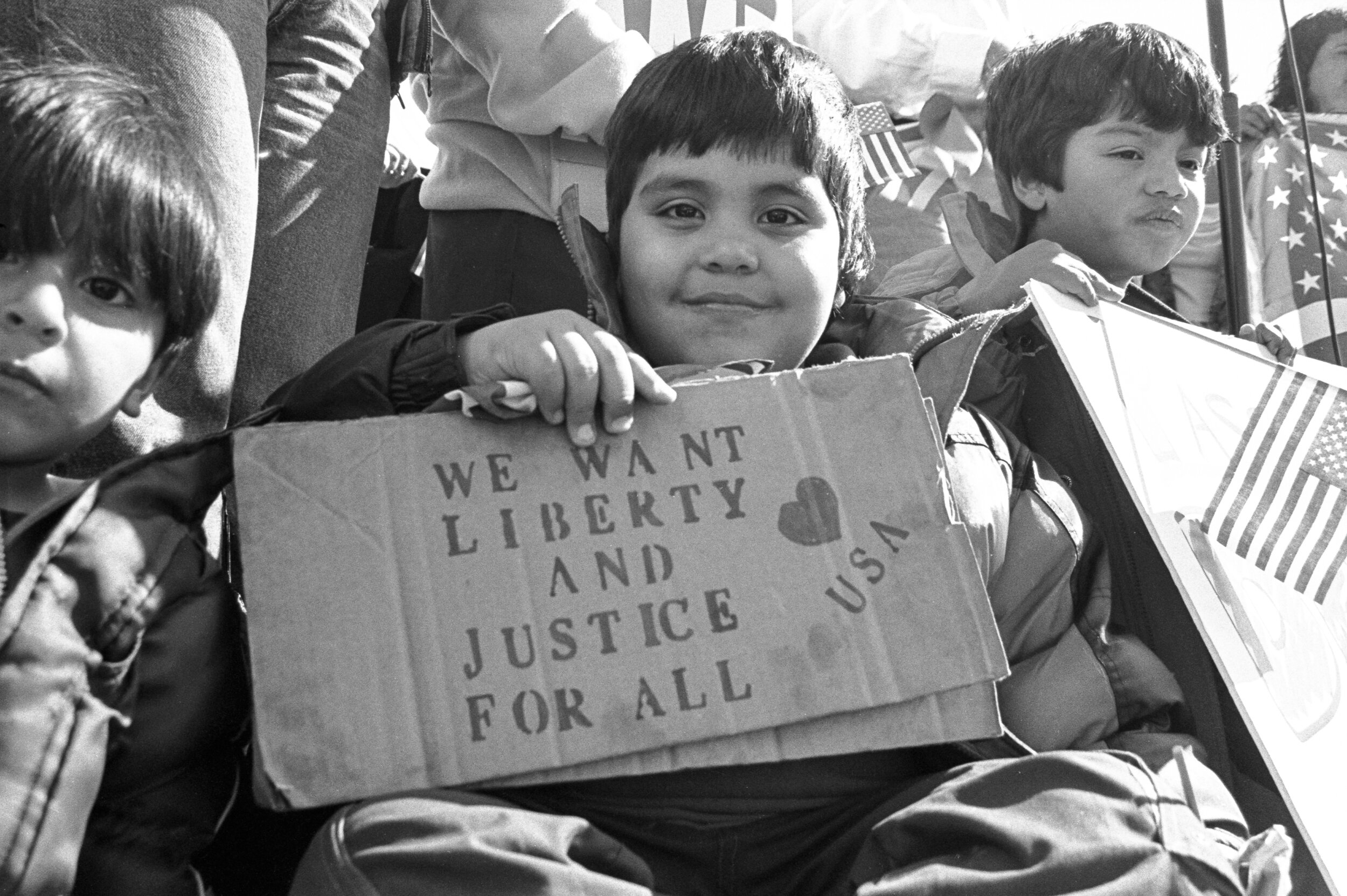

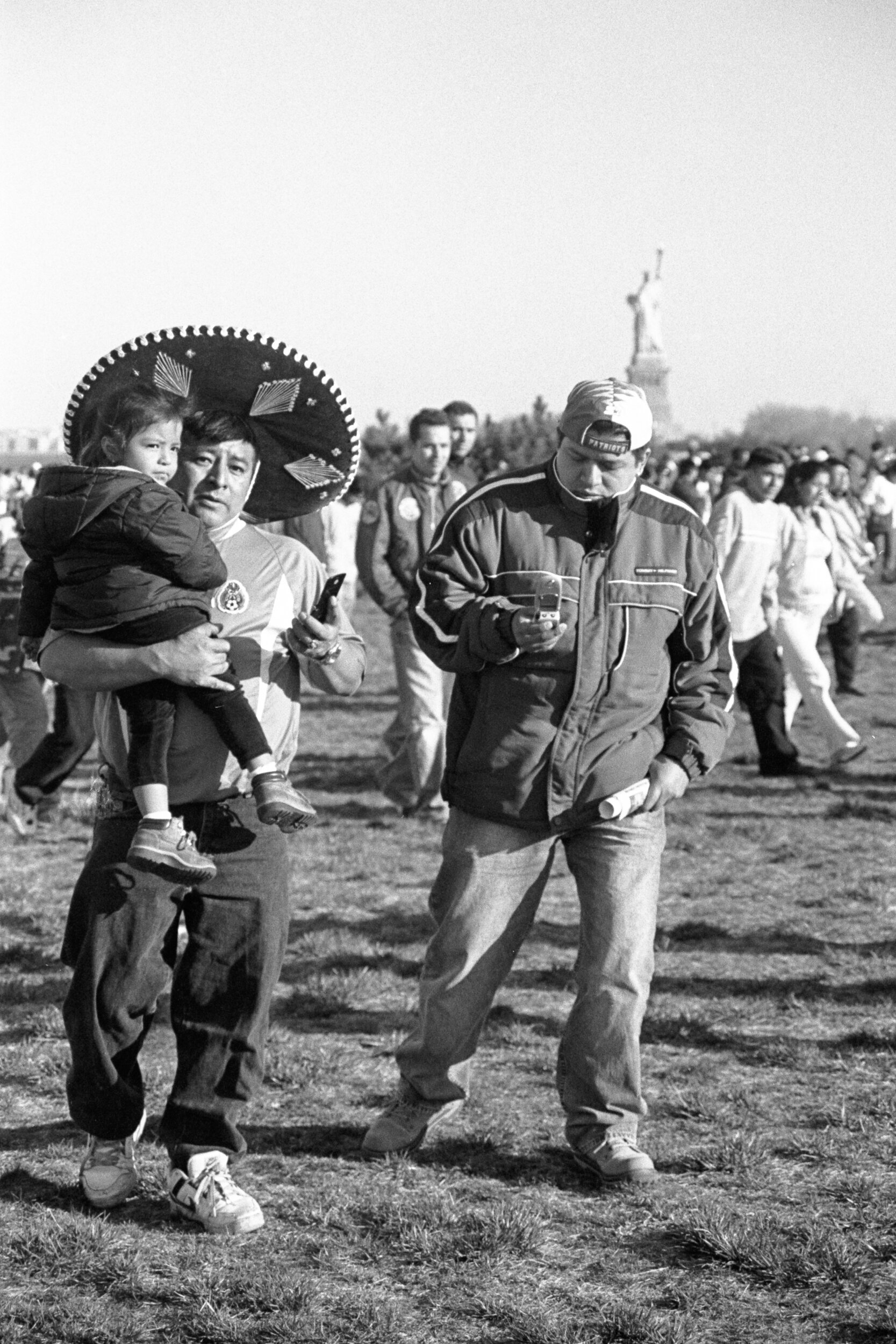

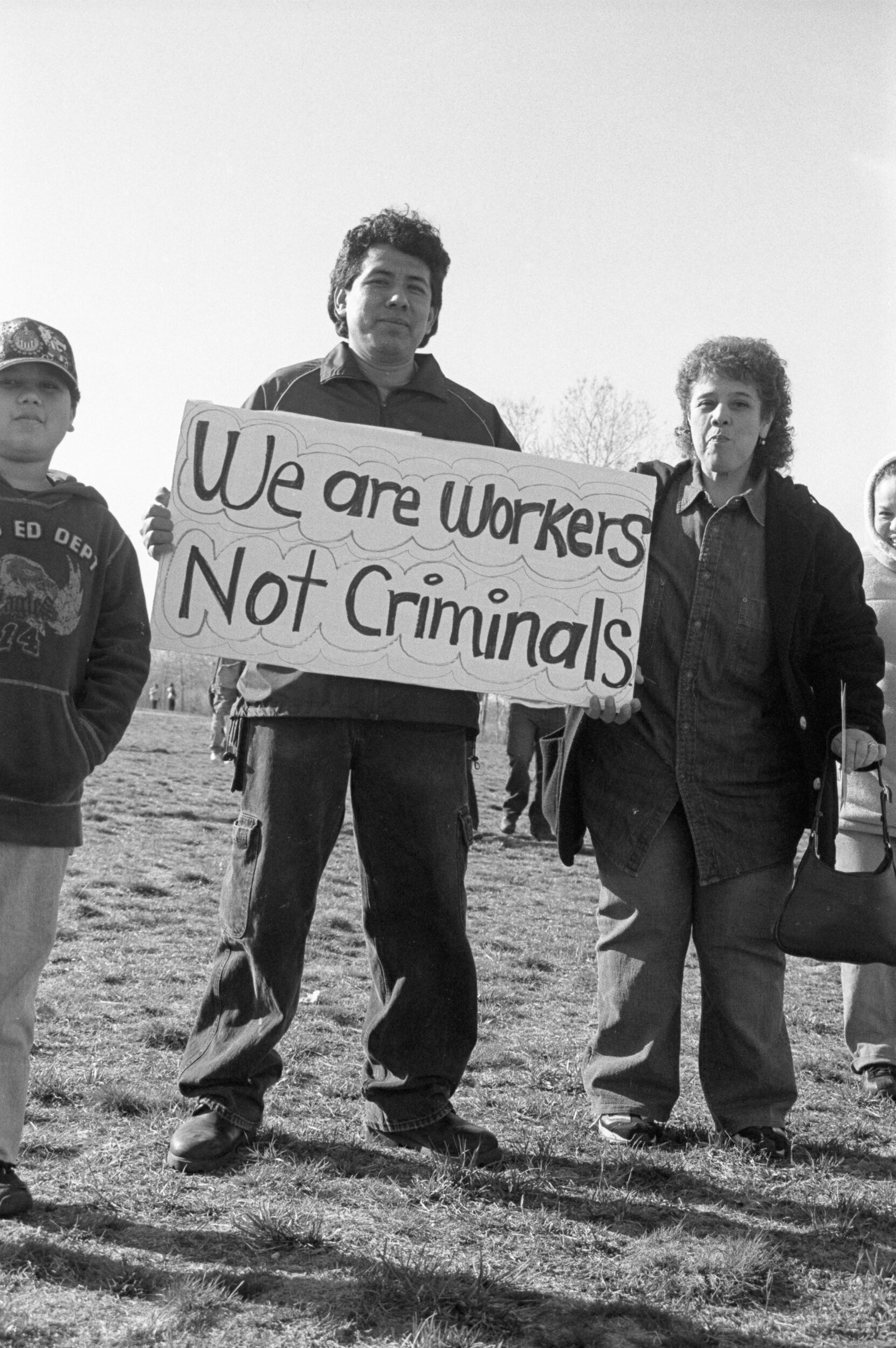

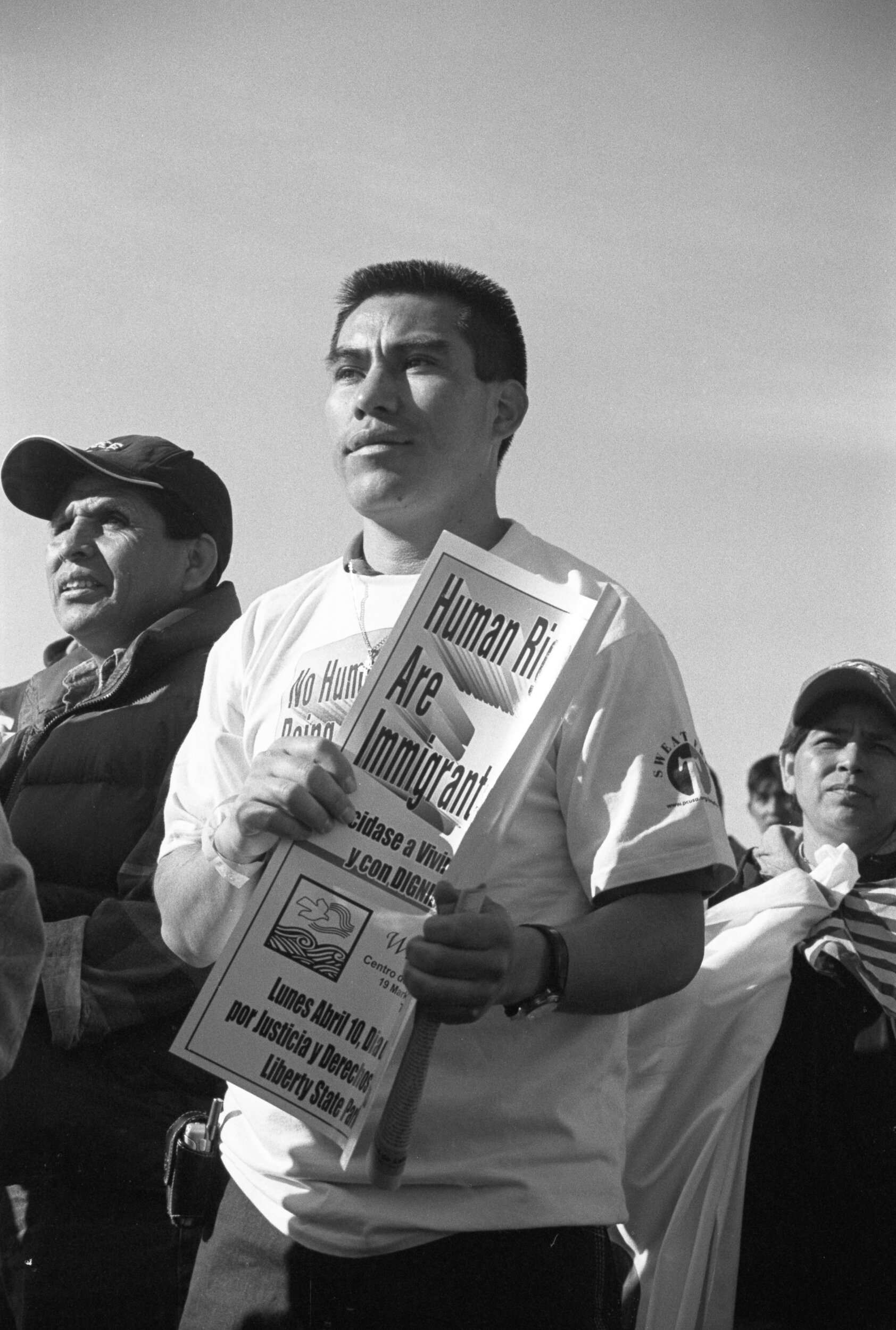

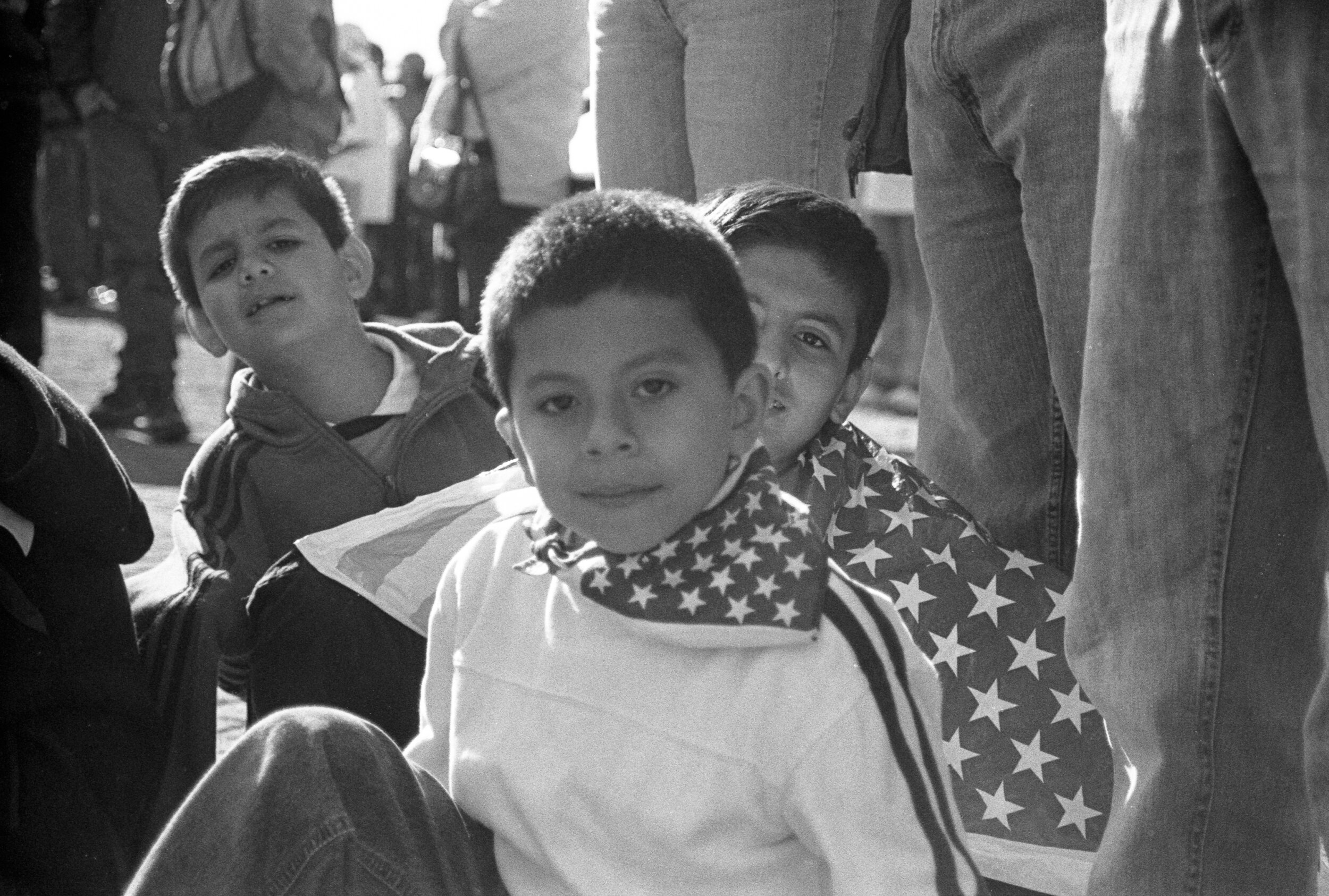

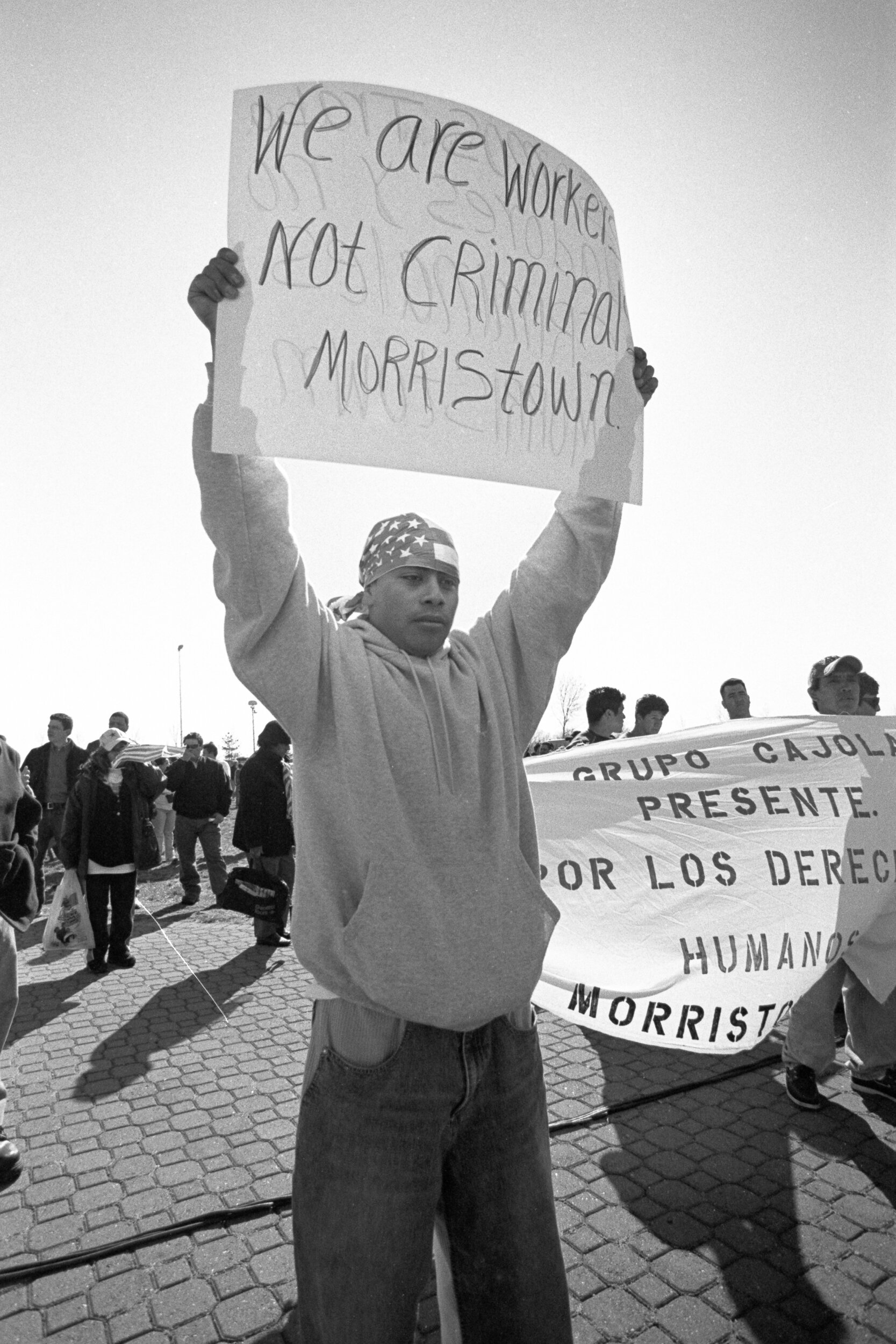

Workers, Not Criminals: Stand Up For Immigrant Rights Rally

Jersey City, NJ 2006

-text below gallery-

Workers, Not Criminals

Summer 2008

For a country where the vast majority of our population has descended from immigrants, it never ceases to amaze how the blame for America’s economic and social woes will without fail point toward the most recent wave of immigrants, generation after generation. Many people whose hard working immigrant family members, only generations earlier, were slandered for “taking jobs from real Americans,” being “criminals,” “lazy freeloaders,” “political subversives” or “unable to adapt to the American way of life,” without a shred of irony, will often berate the most recent arrivals on our shores with exactly the same statements; it is regretfully almost a rite of passage in the process of American assimilation.

The perceived threat of immigrants undermining the economic stability of established working people in our country has been one of the main contributors to what would seem to be an obviously hypocritical resentment. In conjunction with xenophobia and racism, these tensions tend to increase in times of economic and social anxiety. The last several decades in the United States has brought with it extensive deindustrialization, the decline of unions and wages, and increased globalization and automation, economically upending many formerly middle class Americans. Though immigrant groups tend to be some of the most vulnerable in our population, with often limited economic and political power, their visibility in our society as an “other” makes them an easy scapegoat for these economic ailments, even if they have zero logical connection to most of these issues. Many recent immigrants have arrived in our country after being displaced due to some of the very same global economic trade policies that have hurt so many Americans.

In most recent decades, Mexican migrants remain a central target of immigrant vilification. Though today their condemnation has been mostly carried out with the seemingly neutral and discerning term of “illegals,” there is no question of who this term is directed at when used. The mismatch between high demand for Mexican labor and the limited number of legal working visas issued to Mexicans has caused the population of undocumented workers to climb significantly over the last several decades. The previously circular flow at the southern border, where an overwhelming majority of temporary Mexican workers returned home under the US government’s WWII era Bracero program (a labor arrangement that was wrought with exploitation in its own right), was halted by new enforcement protocols in the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. The increased risks and expense of attempting to re-enter the United States that followed this act, coinciding with economic turmoil in Mexico in the decades following NAFTA and the expanding demand for cheap labor in the swelling US service industry created a scenario where these workers were circumstantially left with little option.

The simultaneous demand and marginalization of undocumented workers from Mexico and other parts of Latin America has left them in our country without many of the rights held by documented immigrants and US citizens, putting them in the position of having to accept the lowest paying jobs, commonly with poor working conditions and no benefits, leaving many below the poverty line and uninsured. These workers are also reluctant to complain about abusive situations with employers out of fear for losing their jobs and the threat of deportation. While wages in the US are much higher than in Mexico, the cost of living in the US makes those comparably high wages barely enough to survive on, leading to a miscalculation that often leaves many with disappointing remittances and dashed hopes of a quick return to their country. These unintended extended stays have resulted in workers putting down roots, raising families in the US and having thousands of children who are American citizens, with parents who have no legal standing in the country.

These immigrant workers who are vilified by politicians and the media for being criminals are statically less likely to commit crimes than native born citizens. The claims that they take American jobs are largely outlandish, as very few Americans would take on the back-breaking work done by these migrants for the pay they receive. They are not freeloaders of the system, undocumented workers will commonly pay into the Social Security system with false numbers, for which they will never receive benefits and have little to no access to any government services in most states in the country.

Undocumented workers have been left in legal purgatory and this has a detrimental effect on our society. Not only does it threaten to destabilize thousands of families in this country, it makes these people more vulnerable to crime, since reporting incidents to authorities could put them at risk for deportation. In addition, the inability to obtain health insurance overburdens many emergency departments and hospitals that provide for these communities.

There are many that argue that providing a form of amnesty to this growing population, upon which our economy has come to depend, would be “rewarding lawbreakers.” Much of this sentiment comes from families with immigrant roots themselves, who believe it would be historically unfair to allow them to stay and can’t understand why “these people '' don't respect the law. Many people proclaim that their family, especially those with European ancestors who immigrated in the decades around the turn of the last century, came here “legally” or did it “the right way,” but they often hold these beliefs based on mythology, not historical reality.

If the immigration system we have today had been in place during the great waves of immigration at the turn of the last century, many people’s ancestors would have positively not qualified to enter America. Many more would not have been able to afford the prohibitive costs of filing for the associated fees and lawyer expenses it often takes to obtain a green card, even if deemed qualified. Furthermore, these costs are endured often after sitting on a waiting list for as long as ten years.

For those who have a family immigration story from Europe that began before the early 1880’s, there were virtually no laws to break when entering the United States. With exception to the complete exclusion of Chinese people in 1882, the restrictions for being able to enter the country over the next several decades were limited to things like having a contagious disease, being politically radical, being a convict and illiteracy. These things were also commonly lied about, with little means of verification at ports of entry in those days.

Of the millions of immigrants who passed through Ellis Island in this era, only one percent of migrants were excluded. There were no “numerical limitations” on immigration, no requirements to have an existing family member in the country or any source of employment.

It wasn’t until the Immigration Act of 1924 that one needed a visa from a foreign consulate before admission. It was this same year that set a numerical system capping “undesirable” immigrants, which translated to a targeted reduction in Southern Europeans like Italians and Greeks and Eastern Europeans like Poles and Jews from the region, as well as an expansion of restrictions on other non-European countries. As a result of these restrictions, immigrants of various backgrounds began “illegally” entering the United States through Mexico, Canada and, in some cases, by hiring smugglers to shuttle them in from Cuba.

In the decades following, a national registry program was developed in attempts to remediate this growing population of undocumented immigrants. Based on merit and an ability to pay a fee, it granted amnesty to hundreds of thousands of undocumented European immigrants. Discretionary suspensions in the 1940-50’s further prevented thousands of undocumented Italians and Germans from being deported in the years leading up to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 which abolished discrimination based on national origin. Though the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 led to restrictions that would only exacerbate the growth of undocumented immigrants, it also again gave amnesty to 2.7 million undocumented immigrants, many again who were of European ancestry.

Undocumented immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Latin America, just like every wave of immigrants before, want a legitimate and legal way to make a better life for themselves and their families in our country. We have an immigration system today that is unjust and unharmonious to the realities of the current demands and worker backlogs. It is a system that criminalizes this shadow workforce, while often looking the other way at the employers who create the massive demand that compels this labor supply to arrive in our country. If this mismatch of demand for labor continues to exist, as it currently does in many industries, a legal route must be enacted so these workers are not perpetually marginalized.

Much of what stands in the way of the major reform that is needed to create a safe and fair immigration system is the political risk of advocating for a group that is disparaged by such a large number of Americans. President George W. Bush, a devout conservative, made strong appeals to create a path to citizenship for the undocumented people of this country, as opposed to the mass deportation supported by many in his party. The efforts to compromise in a bi-partisan manner have failed to materialize with the passing of any immigration reform during his eight year tenure. As a result, the lives of these undocumented workers continue to be used as a political tool to play off of the historic resentment that established citizens have toward these immigrants. This struggle will likely continue, until it is hopefully realized by the vast majority of Americans, that these immigrants, just like their own immigrant ancestors, are workers, not criminals.

"1986: Immigration Reform and Control Act," Library of Congress, 1/1/07, https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/irca

Alejandro Portes & Ruben G. Rumbaut, Immigrant America: A Portrait, (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2006)

Daniel Griswold, "Willing Workers: Fixing the Problem of Illegal Mexican Migration to the United States," CATO Institute, 10/15/02, https://www.cato.org/publications/trade-policy-analysis/willing-workers-fixing-problem-illegal-mexican-migration-united-states

David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness. (New York: Verso, 1991)

Dinnerstein, Leornard & Frederic Cople Jaher, eds. Uncertain Americans.( New York: Oxford University Press, 1977)

Doris Meissner, "U.S. Temporary Worker Programs: Lessons Learned." Migration Policy Institute, 3/1/04, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/us-temporary-worker-programs-lessons-learned/

Douglas S. Massey, "Why Does Immigration Occur? A Theoretical Synthesis." In The Handbook of Migration: The American Experience, edited by Charles Hirschman, Philip Kasinitz, and Josh DeWind, 34–52. Russell Sage Foundation, 1999. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610442893.9.

John Bowe, "Does Slavery Exist in America?" The New Yorker, 4/21/2003, http://www.ciw-online.org/2003_New_Yorker_Article_on_CIW_4-03.pdf

Marc Rosenblum, "U.S. Immigration Policy: Unilateral and Cooperative Responses to Undocumented Migration." Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation , January 5, 2000, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4kv9554b

Nelson Lichtenstein, Strasser, Rosenzweig, Who Built America? Working People and the Nation's Economy, Politics, Culture and Society, Stephen Brier, (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2000)

Roger Daniels, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, (New York: First Perennial, 2002)

Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of Immigration, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994)

Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Vol. II. (New York: International Publishers, 1955)

Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Vol. III. (New York: International Publishers, 1964)

Perry L. Wee, The White Ethnic Movement and Ethnic Politics. (New York: Praedger Publishing , 1973)

Reed Ueda, Postwar Immigrant America. (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s Press, 1994)

Saskia Sassen, "America's Immigration 'Problem'" World Policy Journal, , Vol. 6 No. 4 (Fall, 1989) Duke University Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209134

*Updated 2009

*Laura Agustin, "Why 'My Family Came Legally' Probably Isn't True," The Naked Anthropologist, 12/26/08, https://www.lauraagustin.com/why-claiming-my-family-came-legally-is-often-a-myth