Prison Work

New Jersey 2007

-text below gallery-

Prison Work

March 6, 2018 / Updated October 10, 2020

The United States has the highest incarcerated population in the world.

Our total incarcerated population and per capita incarceration rates exceed those of the populous authoritarian regimes of China, Iran and Russia, though our crime rate is on par with most of our democratic counterparts. Though we still far exceed them, the closest countries in per capita incarceration rates are El Salvador, Turkmenistan and Rwanda.

Prison labor has been a part of our penal system since its inception. It has long been accompanied by the "bonding" out of prison labor to private industry, which for decades flourished in the post-Reconstruction era, essentially re-enslaving hundreds of thousands of African-Americans in the form of the peonage system. The 13th amendment, the same constitutional revision responsible for the abolition of slavery, also enshrined prison labor into our constitution: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime.” This has since provided United States federal and state governments, as well as private contractors, with a captive domestic workforce that today yields labor costs comparable to under-developed nations. It may surprise many people to learn that they consume mainstream products from major brands that were partially sourced through inmate labor, where a fellow American was paid an approximately 62 cents per hour on average, or sometimes nothing, for their compulsory labor.

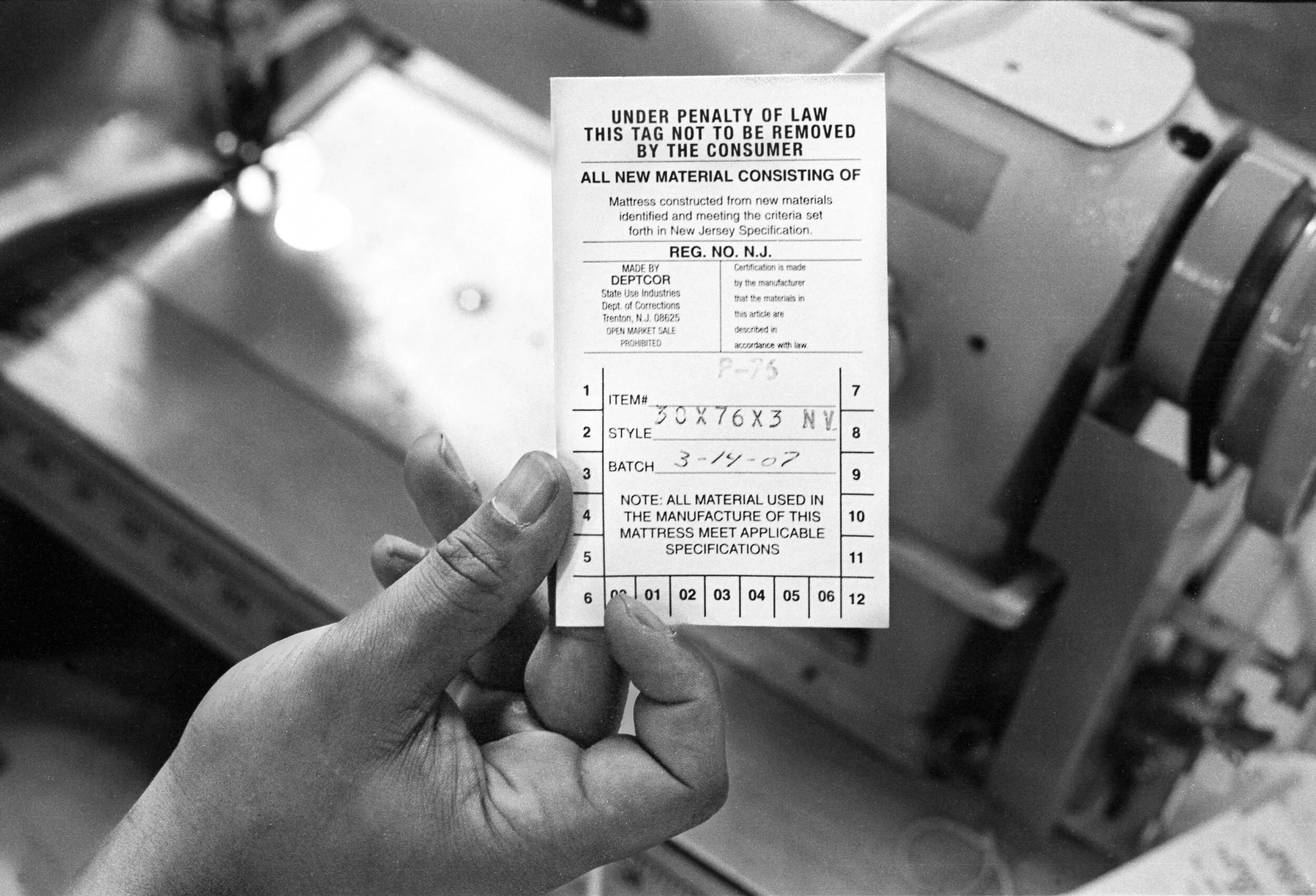

In New Jersey, where I photographed inmates in work programs sewing pillows, mattresses and uniforms, as well as constructing furniture, laws prohibit the selling of these products on the open market, therefore limiting these privately contracted products to in-house and government consumption. New Jersey is also one of the higher paying states for prisoners, with top earners maxing out at a meager $2 an hour. Many prison work programs will then deduct room and board or other petty expenses from these already miniscule earnings.

Private contractors and their government liaisons argue that these work programs help prepare inmates for transitioning back out to the world, lower recidivism rates and increase chances of employment once released. These companies do provide some statistical evidence that this is the case, though the percentage of change is fairly narrow for recidivism and employment claims are largely unsupported by data. What we do know for sure, is that low paid penal workers help to support a multi-billion dollar private incarceration industry. Whether manufacturing products, agriculture work or telemarketing or the largest source of inmate “employment,” the day to day tasks of maintaining a penitentiary, inmate labor in conjunction with our contracted tax dollars result in large profits for powerful corporations and their investors.

The politics surrounding the “War on Drugs'' and the subsequent era of mass incarceration adds one of the most concerning dynamics to the modern era of prison labor and private prison profiteering. Many media outlets, as well as scores of politicians, will commonly spotlight stories of violent offenders being released by a "soft" or "lenient" justice system, only to recommit violent crime once free. This no doubt does occasionally happen, but these anecdotal stories paint a drastically different picture of our justice system than the statistical reality.

Over the last 40 years, our incarcerated population has increased nearly 500%, while our overall population has only grown approximately 30%. According to the research of Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow, minor drug possession charges contributed to a lion’s share of these increases federally, with small marijuana possession accounting for 80% of the drug conviction spike in the 1990’s. Although the rates at which black and white people use and sell drugs are nearly identical, specifically tailored laws and biased public policy resulted in the harsh over-criminalization of poor communities of color, specifically men in the African-American community. Alexander states, “Human Rights Watch reported in 2000 that, in seven states, African Americans constitute 80 to 90 percent of all drug offenders sent to prison. In fifteen states, black men are admitted to prison on drug charges at a rate from twenty to fifty-seven times greater than that of white men.” With harsh mandatory minimums and statutes like “three strike laws” that contributed to increased life sentences (life sentences nearly quintupling since 1984), America’s sentencing for drug crimes are more than many other countries impose for murder.

“Broken Windows” and “Stop and Frisk” policies reaffirmed the long term law enforcement occupation endured by many low income communities of color. Though these policies were theoretically aimed at curbing the real violent crime suffered in these communities, the elevated incarceration rates they produced often further destabilized these neighborhoods and did nothing to address the root causes of violent crime, nor did they have any significant effect on crime overall nationally. This over-policing of black communities has resulted in, quoting Alexander, “more African-American adults [now being] under correctional control today …than were enslaved in 1850.” Overall, these targeted policies have resulted in black men being six times more likely to be imprisoned than white men; for Latino men the rate is nearly three times. A report in 2000 showed African-American youth, with no prior incarceration experience, are six times as likely as white youth to be sentenced for identical crimes. Though personal responsibility is surely a factor in every person’s life, it is clear the margin for error when making a mistake is drastically different in the United States depending on one’s race and economic background.

The rise of this racially biased mass incarceration dovetailed with large increases in state and federal corrections expenditures, the expanding adoption of the private incarceration industry in much of the country and its corresponding explosion in profits. From a business perspective, it is obviously in the greatest financial interest of private prisons and the pyramid of contractors and investors they sit on, to further encourage the sky rocketing of incarceration rates through the continued tactics of over-criminalization, longer sentencing and even efforts to maintain recidivism. And they have done their part in successfully lobbying federal, state and local politicians over the last several decades to meet these ends. Politicians are commonly wooed in supporting the expansion of the private prison industry with the promise of bringing jobs to economically depressed, rural districts of the nation (particularly in most recent years with the expansion of immigration detention centers). This is criminally ironic being the excessive locking-up of Americans from economically impoverished communities of color becomes the source of these jobs. With mass incarceration disproportionately falling on black and brown communities, their human captivity has essentially become a commodity of the market; a peonage system with a different face.

Five of ten constitutional amendments in the Bill of Rights regard the justice system, its proceedings and our rights within it. The framers placed a prioritization on preserving rights and liberties within our country's justice system, though this has never truly been extended to all of its citizens. A broken justice system results in a broken democracy. Our justice system is currently broken. Every American should be outraged at the overt violations of human rights and constitutional betrayal the last several decades of mass incarceration has produced; it should be disavowed as fundamentally un-American.

Fortunately, incarceration rates have begun to decline over the last decade, bail reform is beginning to make headway throughout the country and calls to end the private prison industry continue to grow, but this does not erase the decades of repression and the families decimated. We would also still need nearly 4 out of 5 prisoners to be released to bring per capita prison populations back to 1970’s levels. Just as cannabis corporations have begun to make gigantic profits from the newly blossoming legal marijuana industry, in the face of so many who have been historically imprisoned for small possession convictions of the same drug, the soaring profits made in the era of mass incarceration by the private prison system seem like a great potential funding source for Reparations.

Returning to the subject of prison work, as Americans we need to ask ourselves what is the point of the continuance of this low pay prison work? Is it to exploit disturbingly low paid workers for cheap government furnishing and private telemarketers or is it to truly rehabilitate people and curb recidivism? One would think that even if paid minimum wage for their labor, inmates working would have some money to send to their families or help transition them back to society upon the end of sentence. Potentially, would this not be a more efficient dedication of correctional tax funds for successful rehabilitation and reducing crime? In Michel Foucault’s work on penal systems, Discipline and Punishment, where he argues that poverty is the true root of the recurring cycle of crime and recidivism, Foucalt observes that if one of the main goals of prison is a presumed path to rehabilitation, the high rates of recidivism we experience have obviously made this aspect a complete failure; the absence of addressing poverty is the premier breakdown of our correctional system.

To assume that most prisoners need “rehabilitation” is also questionable when so many who have been put into the system were so commonly brought in due to the lack of economic opportunity and over-criminalization of the often low-income communities of color in which they grew up. There are also scores of people in lock-up across our nation who have yet to even stand trial because they simply cannot afford bail. Statistically, tens of thousands of inmates are completely innocent, but took plea deals due to the threat of high mandatory minimums and lack of resources for effective representation, and who also have to suffer the consequences of being a convicted felon upon release. Many inmates from low income communities now participating in prison work programs could have deeply benefited from true job training and economic engagement prior to whatever circumstances lead to their conviction.

In the absence of comprehensively funded mental health services in many parts of the country, prisons have also become our societies largest de facto residencies for those struggling with mental illness or addiction issues, and tend to provide negligible treatment services, if any. It is estimated that half of our country's incarcerated population suffer from mental illness. The comparative lack of access to adequate mental health care or addiction counseling in low income communities, only results in the further criminalization of this same population.

I would also ask, relating to the tasks being performed in the photographs, have you seen many decent paying job listings for sewing mattresses and assembling prefabricated furniture lately? There is an obvious disconnect between the “job training” aspect of much of the prison work being done and the job market this work is theoretically preparing them for. Being that it is legal to discriminate in employment for having non-violent felony convictions in most states, even if those sewing jobs did exist, it would be difficult for many former inmates to obtain them anyway. In regards to those who served their time but have non-violent felony convictions on their record, I ask what is the societal benefit of restricting their right to vote or serve on a jury, allowing them to be legally discriminated against in employment and housing, denying them access to student loan programs or the revoking of their driver’s licenses? These civic restraints only create further obstacles in achieving economic independence upon reentering society. To again quote Michelle Alexander, “No other country in the world disenfranchises people who are released from prison in a manner even remotely resembling the United States.”

Around 80% of criminal defendants in this country are classified as “indigent.” If a major goal of prison is truly aimed at rehabilitation and reducing recidivism, it needs to be training people for economic success, which includes the need for comprehensive mental health services to be successful. If there had been a national goal of bolstering economic opportunity in the poor communities of our nation, prioritized as militantly as the “War on Drugs” was 40 years ago, we would be living in a drastically different country today. Our bloated correctional budgets, that have allowed the private prison industry to make gargantuan profits, badly needs to be redirected towards economic development, mental health and educational resources in underserved communities in order to even begin to undo decades of devastation and change the course for future generations.

“More money is put into prisons than into schools. That, in itself, is the description of a nation bent on suicide. I mean, what is more precious to us than our own children? We are going to build a lot more prisons if we do not deal with the schools and their inequalities.” - Jonathan Kozol

"…rage arises from the enormous prison gulag-leviathan that squats over the country in an obscene and hypocritical extension of the old slave regime. Six million are under correctional supervision. Six times as much money is spent on prisons as on education"- Peter Linebaugh

"48 CFR § 52.222-3- Convict Labor." Legal Information Institute, 5/22/03, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/48/52.222-3

"Access to Mental Health Care and Incarceration." Mental Health America, 8/2016, https://www.mhanational.org/issues/access-mental-health-care-and-incarceration

Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name (New York: Anchor Books, 2008)

Eileen Poe-Yamagata & Michael A. Jones, "And Justice for Some," National Council on Crime and Deliquency, April 2000

"Factories with Fences: 85 Years Building Brighter Futures." Unicor, 2017, https://unicor.gov/publications/corporate/FactoriesWithFences_FY19.pdf

"Highest to Lowest-Prison Population Rate." World Prison Brief, ND 2018, https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010)

Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1995)

Peter Kerwin, "Study finds private prisons keep inmates longer, without reducing future crime." University of Wisconsin-Madison, 6/10/15, https://news.wisc.edu/study-finds-private-prisons-keep-inmates-longer-without-reducing-future-crime/

Peter Linebaugh, The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016) p. 161

"Private companies producing with US prison labor in 2020: Prison labor in the US, Part II." Corporate Accountability Lab, 8/5/20, https://corpaccountabilitylab.org/calblog/2020/8/5/private-companies-producing-with-us-prison-labor-in-2020-prison-labor-in-the-us-part-ii

"US Prison Population Trends 1999-2015: Modest Reductions with Significant Variation." The Sentencing Project, 5/24/17, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/u-s-prison-population-trends-1999-2015-modest-reductions-significant-variation/

Wendy Sawyer, "How much do incarcerated people earn in each state?" Prison Policy Initiative, 4/10/17, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/10/wages/

*Updated statistics, 2020

*"Calling Out Companies That Use Prison Labor." GlobalTel, 10/25/19, https://blog.globaltel.com/companies-use-prison-labor/

*John Gramlich, "Black imprisonment rate in the U.S. has fallen by a third since 2006." Pew Research Center, 5/6/20, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/share-of-black-white-hispanic-americans-in-prison-2018-vs-2006/

*Wendy Sawyer, "Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020." Prison Policy Initiative, 3/24/20, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html